Former San Diego Charger Undergoes TAVR

NFL legend “Big Ed“ White has transcatheter aortic valve replacement at Scripps

NFL legend “Big Ed“ White has transcatheter aortic valve replacement at Scripps

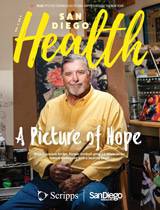

Ed White is a strategic thinker. A legendary offensive guard for the San Diego Chargers and Minnesota Vikings, “Big Ed” played 241 regular season NFL games, plus four Pro Bowls and four Super Bowls. His Vikings were NFL champions in 1969. He studied his opponents, worked out his aches and pains, went out on the field and got it done.

White took a similar approach when preparing to have his aortic valve replaced. He studied the problem, consulted with family and experts and chose what he thought was the best approach to restore his heart health.

Living with aortic stenosis

The problem was stenosis—his aortic valve had narrowed and was obstructing blood flow. The condition was having a big impact on his quality of life. Without enough oxygenated blood, White had trouble pursuing the hobbies he enjoys most in retirement, hiking and painting.

“I’ve known for several years that I have a murmur,” says White. “It came from a blocked valve, a thing that’s been passed down from my father to me. My brother has it as well. The last couple of years, there were things happening with my breathing. I was breathing in, but it didn’t feel like I was getting any oxygen.”

He had an equally serious concern on top of that. About a year ago, he was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s, and several studies have shown the condition may be linked, at least partially, to cardiovascular disease. To hold the line against Alzheimer’s, he needed to boost his heart function.

White adjusted his diet and kicked up his exercise regimen, which helped a lot. He was feeling pretty good when he and his wife took a cruise to Panama to celebrate her 70th birthday. But on the way back, his heart took a bad turn.

“I ate too much salty food on the cruise, and my heart couldn’t handle it,” he says. “The fluids built up around my heart and lungs, and I had heart failure.”

Though he recovered, he knew something had to be done about his valve stenosis. At 72, White has no desire to slow down. In addition to being physically active, he’s a devoted writer and artist, producing canvases both realistic and abstract—boats, nature, classic cars and, of course, his beloved football.

“It’s my passion,” he says. “I don’t think of it as work; it’s an extension of who I am. I listen to Tibetan music and go into a meditative state. It’s a good world.”

Aortic valve replacement options

Aortic valve replacement options

“I’m a big guy who’s pretty active. I want to be active for as long as I can.”

Ed White, Former San Diego ChargerWhite knew the most effective treatment for a bad aortic valve is to replace it, but there are a couple of ways to get there. Heart valves have traditionally been replaced during open heart surgery, which is quite effective. But he was reluctant about this option, concerned that the long recovery might set him back.

“Too many of my friends have gone through opening up the chest, and it really affected them,” he says. “I’m a big guy who’s pretty active, and I don’t want to slow down for any amount of time. I want to be active for as long as I can.”

The other choice was a transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR). The procedure guides a catheter with a new valve through a small incision into a patient’s blood vessels and on to the heart. This collapsed valve is then expanded and implanted, pushing the bad valve aside and restoring blood flow.

TAVR procedure was still considered experimental

TAVR has many advantages, including fewer complications compared to open surgery. Most importantly for White, it offers a much faster and easier recovery.

The only problem was timing. The US Food and Drug Administration had approved TAVR for high- and medium-risk patients—people who might not be able to tolerate the rigors of an open surgery— and White fell into the low-risk category.

“I couldn’t do TAVR because I was in good health and would survive open heart,” he says. But he was determined to find another way.

Fortunately for White, Scripps has been a TAVR clinical trial site since 2007, conducting some of the research that ultimately earned the procedure FDA approval for high- and medium-risk patients. They were also hosting a trial for low-risk patients like him.

But it wasn’t a perfect fit. To know whether the new treatment is better, clinical trials require a control group. If White entered the trial, he could’ve been randomly assigned to either the TAVR group or the open surgery group.

He wanted to figure out all the angles: the right procedure and the right people to perform it. He started his due diligence with his brother, a professor of medicine. He also spoke with his personal doctor, Lee Rice, DO, who has been lead physician for the Chargers and countless other professional athletes. He queried specialists he knew at the Cleveland Clinic. They all told him that TAVR was probably best for his situation, and that he was in great hands at Scripps.

FDA approves TAVR for low-risk patients

So, White decided to wait. Despite the problems he’d experienced on the cruise, he was feeling okay, and it seemed apparent that the FDA would soon approve TAVR for low-risk patients. He redoubled his exercise routine—approaching it the same way he handled his NFL training camps. He would take the best possible care of himself until the FDA made their decision.

On August 16, 2019, the FDA approved TAVR for low-risk patients. Wasting no time, White scheduled his procedure for September 3.

“This procedure has revolutionized heart valve surgery by giving patients like Ed a much less complicated option for treatment that doesn’t involve the prolonged recovery of open-chest surgery,” says Paul Teirstein, MD, chief of cardiology, Scripps Clinic, and medical director, Prebys Cardiovascular Institute, who led the team that performed White’s TAVR.

Although no procedure is routine, Dr. Teirstein and his colleagues have been performing TAVR for years and they were confident in a good outcome.

A sophisticated surgery and a simple recovery

As White was being wheeled into the cardiovascular catheterization lab, he knew it was time to trust his physicians. He had done his due diligence, had carefully selected the procedure and the people to perform it. Time to let go.

“I have a strong belief that God is in control,” White says. “I did all I could do as far as being at the right place at the right time with the right people. That’s all I could control.”

White left the hospital the day after his procedure, which is normal. Two days later he walked half a mile, the first step on the road back to his routine five-mile hikes.

Two weeks after his TAVR, White took a trip to Minnesota for a reunion with fellow Vikings from the 1969 Super Bowl team. Every day he feels a little better.

“I’m back to walking and back to working,” he says. “Everything is back to normal.”

Now that he’s no longer distracted by the faulty valve, White can get back to doing what he loves. He’s grateful for the insights he received from doctors at Scripps and around the country, and for the great outcome at the end of his journey.

“I couldn’t have had better doctors,” he says.

This content appeared in San Diego Health, a publication in partnership between Scripps and San Diego Magazine that celebrates the healthy spirit of San Diego.