How to Improve Digestive Health: Making Friends with Your Microbiome

Why gut bacteria matter and what you can do

Why gut bacteria matter and what you can do

A special relationship between the brain and gut has long been suspected. Think of phrases like “gut feeling,” or “gut instinct.” Studies have shown these aren’t just figures of speech. The gut and brain communicate through a complex system called the gut-brain axis and your beneficial gut bacteria play a vital role in that conversation.

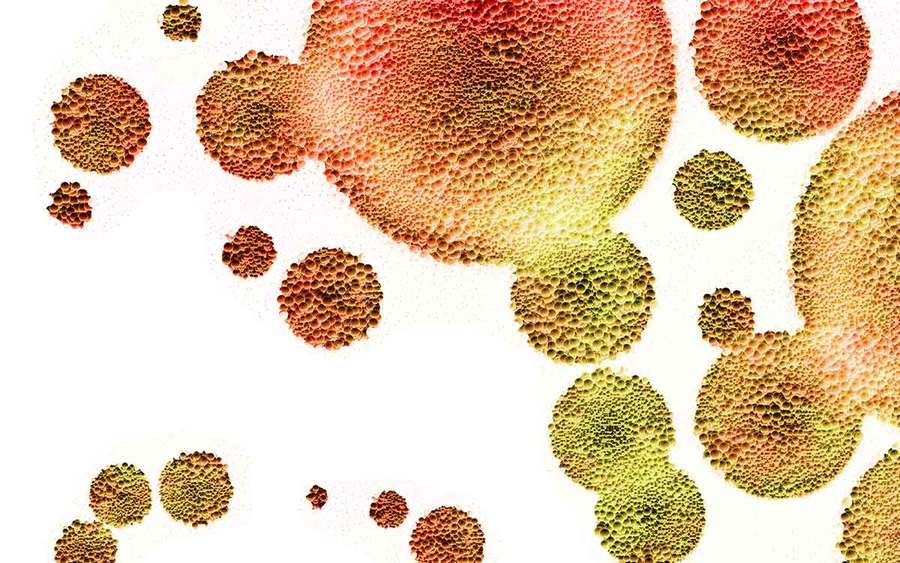

But it’s not just two human organs talking to each other. The gut is colonized by trillions of microbes — including thousands of different bacterial, fungal and viral species — that play a critical role in this constant chatter. A balanced microbial ecosystem can support good health, helping our bodies modulate hormones, neurotransmitters, inflammation and even pain.

On the other hand, an imbalanced system may play roles in cancer, diabetes, inflammatory bowel disease, obesity, depression and many other conditions.

“We are recognizing that when we call the gut ‘the second brain,’ it may actually be the first one,” says Robert Bonakdar, MD, director of pain management at Scripps Center for Integrative Medicine. “This is because what we eat — or don’t eat — can have a significant impact on gut inflammation and the makeup of our gut microbiome, which can send signals to the brain that ultimately affect many aspects of our health, our mood and how we deal with stress and pain.”

Why a healthy diet matters

Gut microbes have long been pigeonholed as either good or bad, but that’s turning out to be a major oversimplification. Like people, gut microbes have their own self-interests to look after, such as finding food and making more microbes. As long as their interests coincide with ours, everything is in balance — a condition scientists call “homeostasis.” But if the system loses homeostasis, bad things can happen.

“We are beginning to find that people who have less microbial diversity — a reduced overall population and fewer types of bacteria — are more prone to inflammatory conditions, including inflammatory bowel disease and certain types of chronic pain,” Dr. Bonakdar says.

Other research shows a link between the microbiome to neurological conditions, including migraines, Parkinson’s and dementia.

“There is really no condition that has not been linked in some way to our microbial community, although the evidence is stronger in some areas,” Dr. Bonakdar says.

Many things may impact the gut microbiome: environmental toxins, stress, disease, even loud noises. However, diet — particularly the so-called Western diet, rich in unhealthy fats and carbohydrates — is likely the greatest offender.

“We know that the standard, highly processed American diet typically depletes important micronutrients and fiber,” Dr. Bonakdar says. “A number of studies have demonstrated that the transition to a Western diet in traditional countries begins to increase the occurrence of certain conditions, including inflammatory bowel disease, which is highly linked to both a reduced number of microbes and a loss of microbial diversity.”

On the other hand, a healthy diet may have a positive effect on the microbiome. Early evidence hints that the same strategies that support the cardiovascular system and glucose metabolism may also help keep the microbiome in balance. In other words, exercise, eat lean proteins, fruits, and vegetables and take steps to mitigate stress.

Include probiotics and prebiotics

As people have become more aware of these gut floras, there’s been increased interest in supporting them. Two approaches are to add microbes through diet (probiotics), or to eat nutrients that support these resident microbes (prebiotics).

Prebiotics are fibers that nourish the beneficial bacteria in your gut. Probiotics are live bacteria that help maintain a healthy balance. Fermented foods, such as yogurt, kefir and sauerkraut are excellent sources of probiotics. High-fiber foods such as apples, broccoli and lentils provide valuable prebiotics to support gut health.

Keep in mind, health varies from person to person, so the most effective approach is to choose probiotics and prebiotics tailored to your specific needs and health goals.

A probiotic that might help in overcoming anxiety may have little effect on inflammation. Any personalized approach should match a targeted probiotic cocktail with a patient’s specific needs.

“I think it is too early to have an absolute take on what individuals should do across the board,” says Dr. Bonakdar. “I tell patients to incorporate many different components in their diet to support good health."

This means eating the rainbow of plant foods, which increases fiber and prebiotic intake, as well as incorporating various fermented foods. Specific probiotic strains may benefit certain conditions. “Talk to a health care provider who can clarify the science,” Dr. Bonakdar says.